A session at the annual conference of the East Asian Society for the Scientific Study of Religion explored how democratic regimes do not always guarantee freedom of religion or belief.

by Massimo Introvigne

An article already published in Bitter Winter on July 15th, 2024.

Conflicts about freedom of religion or belief often derive from conflicts between different notions of morality. The relationship between morality and religion was the theme of the yearly conference of the East Asian Society for the Scientific Study of Religion (EASSSR), held at Reitaku University in Chiba, Japan, on July 6 and 7, 2024, on “Religion and Morality in the Global East.” Speakers examined the crisis of traditional Confucian, Taoist, and Buddhist notions of morality in East Asia, while noting that how ethics and religion are approached remains different in the area with respect to Europe and the Americas, where secularization has not eliminated the presence of a strong Christian heritage.

For Tai Ji Men dizi (disciples) who attended the conference, as they did with other EASSSR gatherings in the past, the comments of several speakers resonated with ideas with which they are familiar. In fact, many lecturers agreed that behind the different approaches to morality one common and universal element is conscience, which is also at the center of the teachings of Tai Ji Men, a menpai (similar to a school) of Qigong, martial arts, and self-cultivation, and of its Shifu (Grand Master), Dr. Hong Tao-Tze.

On the other hand, the fact that many agree on the key role of conscience does not mean that this principle is applied and respected everywhere in practice. Several sessions in the conference dealt with a conflict of moralities, where states regard stability and order as the prevailing values, while religious and spiritual groups ask for liberty based on the primacy of freedom of conscience. This conflict is obvious in totalitarian and authoritarian regimes. However, one session in particular evidenced that the same conflict may also exist in democratic countries, especially those with an authoritarian past. Transitional justice is defined by the United Nations as the set of measures implemented after the transition from a non-democratic to a democratic regime to re-establish the truth on past human rights abuses, indemnify the victims, and punish the perpetrators. This passage is never easy.

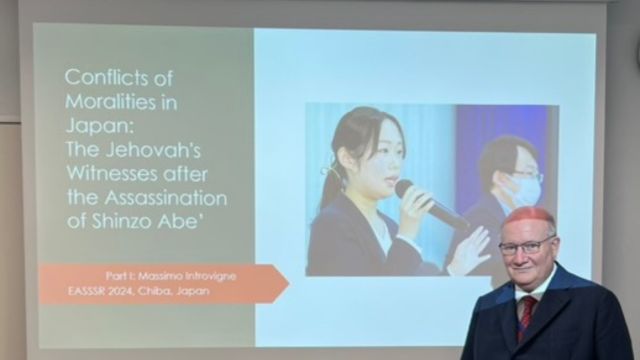

Session 2-1 had as its title “Conflicting Moralities and Religious Controversies in the Global East: Japan and Taiwan.” Holly Folk, Professor and Major Advisor on Religion and Culture at Western Washington University, Bellingham, Washington, and myself discussed the religious liberty crisis in Japan after the 2022 assassination of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. The politician was killed by a man who had a personal grudge against the Unification Church (now called the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification), with which Abe had cooperated through the years. A campaign against “cult” followed, targeting both the Family Federation and the Jehovah’s Witnesses, who were the main focus of our presentation. The post-Abe-assassination crisis, we argued, revealed a typical conflict of moralities in Japan and, as a statement by the United Nations on the issue has recently confirmed, the reluctance of Japanese society and politics to fully accept international standards of freedom of religion and belief. In fact, this reluctance also emerged during the conference, as some Japanese scholars support the campaign of the government against groups stigmatized as “cults.”

Another democratic society with unresolved freedom of religion or belief issues is Taiwan. Tiffany Fang, who holds a degree in Mathematical Statistics and Actuarial Science from Taiwan’s Aletheia University and currently works as a freelancer producing media contents, has been a Tai Ji Men dizi for over thirty-three years. She presented her personal experience of the relationship dizi establish with their Shifu, which is typical of the Chinese tradition and dates back at least to Confucius. It is similar to and may be even deeper than the relationship between a father and his children.

As part of this relationship, dizi give to their Shifu on certain occasions “red envelopes” with money. In martial arts and Qigong organizations in Taiwan it is taken for granted that the content of the “red envelopes” should be considered as non-taxable gifts. However, as part of the 1996 political crackdown on spiritual movements accused of not having supported the ruling party’s candidate in the first democratic presidential elections held in Taiwan, Tai Ji Men’s Shifu, his wife, and two dizi were arrested and the movement was accused of fraud and tax evasion. Prosecutor Hou Kuan-Jen, who started the case, claimed that the content of the “red envelopes” was not gifts but taxable tuition fees for a (non-existing) cram school. Eventually, courts of law, up to the Supreme Court in 2007, found Tai Ji Men defendants innocent of all charges and gave them national compensation for the previous unlawful detention.

However, Fang explained, the National Taxation Bureau (NTB) ignored the Supreme Court verdict and continued to ask Tai Ji Men to pay ill-founded tax bills, based on the false cram school theory. Finally, after protracted litigation, the NTB agreed to correct all tax bills to zero, except one. For the tax bill of 1992, the NTB claimed that a final and no longer appealable decision against Tai Ji Men had been rendered, and the amount should be paid. “Obviously,” Fang said, “the content of the ‘red envelopes’ in 1992 was the same as in the other years.” However, the NTB relied on a technicality and, based on the 1992 tax bill, in 2020 confiscated, unsuccessfully auctioned off, and nationalized land in Miaoli regarded by Tai Ji Men as sacred and intended for a self-cultivation and educational center. Widespread protests followed both in Taiwan and the United States, where Tai Ji Men is also active.

Fang then returned to her personal testimony, reporting how practicing Qigong within Tai Ji Men not only solved problems of relationship between her and her mother but led her and her family to a volunteer activity, most recently by producing animation videos intended to alleviate the fear of COVID-19 during the pandemic, which won international acclaim. Fang concluded that she also experienced the anguish of the unresolved Tai Ji Men case. However, “practitioners of martial arts are not afraid of persecution” and quietly continue to fight for justice and a conscience-based social order.

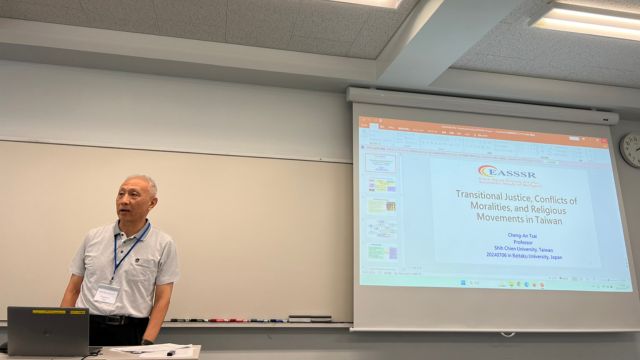

Professor Tsai Cheng-An, of Taiwan’s Shi Chien University, presented the broader context of transitional justice in Taiwan, whose deeper root he identified in conscience. The issue, he said, is worth discussing in a conference on religious studies because the human rights violations in Taiwan that transitional justice should rectify also include violations of freedom of religion or belief. In Taiwan, Tsai said, Martial Law was abolished in 1987 and its last provisions ceased to have effect in 1992. However, as the 1996 crackdown on religious movements demonstrated, the post-authoritarian phase in Taiwan continued well after 1992. Unfortunately, Taiwan’s 2017 Act on Promoting Transitional Justice only covers human right violations that occurred until 1992.

This “timeframe limitation on transitional justice,” Tsai said, is the first of three “lingering poisons of authoritarianism” still plaguing Taiwan. The second is the “timelines limitation on new evidence,” a peculiar interpretation of the statutes of limitations different from those prevailing in other democratic countries. In the Tai Ji Men case, it is argued that the decision on the 1992 tax bill cannot be revised even if it was rendered before the 2007 Supreme Court verdict. Although this should count as “new evidence,” some argue that once a “final” decision has been rendered there is no way of relying on these new elements.

The third “poison,” according to Tsai, is the “perpetual tax bill,” a system allowing tax authorities to ignore decisions by courts of law by continuously reissuing the same tax bills, trying to exhaust the legal and financial resources of the taxpayers until they are compelled to pay. Tsai noted that the “perpetual tax bill” system was criticized by a Control Yuan report released on May 4, 2022, yet no effective reform followed.

Tsai concluded by revisiting the main events of the Tai Ji Men case, where the “three poisons” were at work, and calling for a tax and legal reform in Taiwan that should remove the “poisons,” implement transitional justice, solve the Tai Ji Men case, and ensure Taiwan’s compliance with international human rights and freedom of religion or belief standards.

A panel discussion followed, involving the audience, where the speakers compared the cases of Japan and Taiwan. Professor Folk noted that one important feature of the Tai Ji Men case not discussed in the session (but presented in other sessions on Tai Ji Men of academic conferences she attended) is the immoral system of bonuses given in Taiwan to tax bureaucrats who enforce tax bills. This is a powerful incentive to corruption and makes solving cases like Tai Ji Men more difficult, Folk said. She also answered a question why Tai Ji Men did not simply pay the 1992 tax bill and settle the case, as other groups involved in the 1996 religious crackdown did. She said that this is in general a wrong strategy, as it encourages corrupt bureaucrats to continue in their wrongdoings, which in the future may even target again religious and spiritual groups perceived as “dissident.”

I added that Tai Ji Men never settled also for a question of principle, because the movement did not commit any tax evasion and by settling would deny its own conscience-based principles of upholding truth and justice. Professor Tsai told the audience that unfortunately, while Taiwan has now a new President and government, there are no immediate projects of amending the Act on Promoting Transitional Justice, extending it to human rights violations committed after 1992. This is one reason, Tsai said, international scholars should continue to pay attention to Taiwan’s human rights and religious liberty issues. The Tai Ji Men case itself can be solved only by internationalizing it.

The conference was an opportunity for the Tai Ji Men dizi to meet new friends and to raise the consciousness of the Tai Ji Men case as a representative freedom of religion or belief issue in East Asia.